From the 2020 Collegian | On a January morning, 18 Central High School students sat around a circle of tables in their first period class. It’s silent, but it’s not tense—there’s an air of thoughtfulness, of students searching to find their answer to the question posed moments before. One by one, the students begin to raise their hands, looking at the professor leading the class.

The question? “How does mass incarceration affect you personally?”

Dr. John Giggie, a history professor at UA, calls on one of these high schoolers to begin, motioning that they’ll go around in a circle to discuss. The students don’t have to answer if they don’t want to, but almost every student in the class does in some form or fashion.

The 18 students in the circle make up History of Us, the first high school African American history class in Alabama. Here, students learn about Black history on the local, state, and national levels, tying each unit together with research, social media, discussion, and personal reflection.

Giggie, who teaches classes about lynching, civil rights, and African American history to undergraduate students at UA, is hoping that this class will bring about a new generation of young historians—a generation whose desire to learn the truth about their communities will allow them to bring voices to those who were powerless in the past.

“One goal of this class is to create a new generation of young intellectuals, and also create a generation of engaged citizens,” Giggie said. “History isn’t artificial; it isn’t something stuck between two covers in a book and put on the shelf. Rather, the ideas and experiences of the past deeply affect how we live today. And conversely, often the struggle we experience on a daily basis has historical backgrounds. People made decisions decades ago, generations ago, that impact people today. I want these students to see that.”

Each student was hand-selected for the class by a committee of Giggie, the school principal, and teachers at Central after a rigorous application process. The students were selected because of their dedication to and interest in learning about African American history.

“The class, in general, is really different from any other history class I’ve taken,” Alex Barnes, a junior in the class, said. “We hit points that you don’t normally hit in an American history class. We don’t just talk about the Civil Rights movement—it’s more than that. We’ve talked about slavery and lynching, and also police brutality and mass incarceration. It’s a lot, but it’s been really interesting.”

Giggie, history graduate student Margaret Lawson, and Central High School teacher Jesse Chadwick worked together to create a curriculum that exposes students to African American history both locally and nationally. The team hopes that this method of learning will allow students to think about broader issues and localize them, making it concrete.

“Every unit we’ve done has been framed within Tuscaloosa in a very specific way,” Giggie said. “When we studied slavery, we looked at runaway slaves from Tuscaloosa. When we studied the Civil War, we looked at Civil War issues in Tuscaloosa. We studied ideas of African American history that tend to be left out in American history. When you continually frame issues in a Tuscaloosa or a personal manner, the students’ own lives become fodder for conversation and personal analysis.”

While studying different eras of African American history, the students learned how to conduct in-depth research about local history. During the unit on lynching in the United States, Giggie gave the students the task of choosing a victim of lynching in Tuscaloosa County and finding out their story.

“These students have looked at the history of lynching, and I want to teach them that, as students of African American history, they have a moral obligation to recapture stories that were intentionally meant to be forgotten, and recognize that part of their role right now is to recover history in a very intimate way,” Giggie said. “They’re figuring out why the lynchings happened, but they’re also finding the victims’ humanity: who they loved, where they worked, who they left behind. In researching these lynching victims locally, the students become a voice for these forgotten men.”

Many students voiced their support of the localization of these broad topics, and felt that studying a particular victim of lynching made it feel more personal and real.

“After taking the class and doing the research, I can walk around Tuscaloosa and be like, well, somebody was lynched here,” Jashon Griffin, a junior at Central High, said. “It makes it more realistic, more lasting. You can see how recent lynching and slavery occurred, because it wasn’t that long ago. You can see in your everyday life that it was there.”

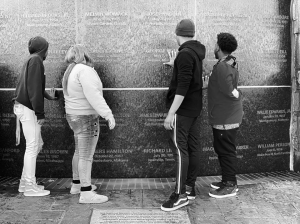

During this research project, the Central High students partnered with UA history majors, using online databases to find whatever they could on the lynching victims they researched. The class also took a trip to Montgomery, where they visited the Equal Justice Initiative. Here, they walked through exhibits about lynching, slavery, and racism in the United States.

As the year progressed, Giggie and Lawson began to incorporate more reflection into the course. The goal was to get students to think about how history affects them today. Leading up to the conversation about mass incarceration, the team assigned students online blogs, short papers, and small group discussions about current social issues.

As the students began to answer the question about incarceration, students brought up familial experiences, being stopped by police, and stories their parents had told them about the criminal justice system. The students shared their own histories, adding them to the collective knowledge of the class and leaving a lasting impression on each other’s understanding of mass incarceration.

To Giggie, sharing these experiences is one of the most important aspects of the class. As a white professor, he recognizes that his experiences are quite different from his students’, and African American history is theirs to tell.

“I believe deeply that personal experience is an essential part of how we understand history and how we live in the world,” Giggie said. “And as a white professor, there are certain things that I can’t teach them about African American history. There are certain experiences they’ve had that I’m never going to have. So I’m in this class, in part, to learn from them. What does it mean to be a young, Black intellectual who’s having to experience mass incarceration? What is it like being a young, Black intellectual who is in a school that is 98 percent African American? I can’t experience that, but I can learn from these students. And because the conversation we have will integrate their experiences and knowledge with my experience and knowledge, it promises to be a richer experience for all of us.”

After spending every day in class with the students, Giggie hopes they have learned the integral parts they play in the shaping of history, whether they’re recovering lost voices or adding their own. And the students hope the class makes a way for more students to learn about their communities.

“History affects all of us,” Iyana Dixon, a senior in the class, said. “African American history affects all of us. I hope that this class will not only open up Tuscaloosa to have a discussion about it, but other cities and counties. Learning about your history does genuinely affect you as a person. It shapes your mind as an individual, whether you take a course about it or learn about it on your own.”

“Every day, Ms. Lawson calls us historians, and I think that’s important,” Barnes said. “Now, I could tell someone how slavery and lynching directly affected me. You can see how it personally affected your daily life, and how it affected you as a person—not just how it played a major role in the way we live today, but how it affected you personally. I feel more confident when talking about my personal testimony because of this class.”

Class Dismissed: Updates from History of Us

Since the end of the 2019-2020 school year, several developments have occurred within the class. The course is being taught at Central High School again, with two teachers teaching the course and Giggie serving in an advisory role. These classes will serve as a blueprint for other schools in Tuscaloosa County for future History of Us classes.

Giggie presented professional development workshops for teachers around the state to adopt the curriculum for their classrooms. One teacher in Decatur will be offering a version of History of Us to eighth graders next year. Giggie also gave five presentations about the class, most recently to the National Conference on Citizenship. Two alumnae of the class, Noa Jordan and Delphia McGraw, also joined in the presentation.

Several students participated in and led marches this summer in the wake of George Floyd’s death, calling for an end to police brutality and a national reflection on racism.

To Giggie, the most important development in the course is a recent collaboration with Rev. Tyshawn Gardner, Vice President of Student Development at Stillman and Pastor of Plum Grove Baptist Church, to found the West Side Scholars Academy. The academy will use the curriculum developed for History of Us as the basis for creating a summer enrichment academy for middle schoolers from Tuscaloosa’s West Side. It will launch during the summer of 2021, asking students to participate every day during the summer and two Saturdays every month during the academic year.