The circumstances of Caroline James’s childhood made a college education look like a fantasy. Until she was placed in foster care as a 10‑year‑old, her home was filled with drug addiction, schizophrenia, and physical and emotional abuse.

She recalls being burnt with irons, punched in the face by her father, and told almost daily that she was ugly, a disappointment, talentless, and stupid. In grade school, she didn’t apply herself and often received bad grades because she thought that by trying, she might prove her father right.

However, despite the disadvantages of her youth, James eventually graduated from The University of Alabama magna cum laude, working with the Blackburn Institute, Alabama REACH, and the McNair Scholars program along the way. She went on to teach fifth grade in low-income areas in Louisiana and received a national teaching award in 2014.

But her most recent achievement has been competing against 9,000 other hopefuls for a place as a Master of Philosophy student at the No. 2 university in the world—the University of Cambridge—and receiving the prestigious international Gates-Cambridge Scholarship to fund the entirety of her education and travel costs.

“It’s the greatest honor to even make it to the interview process,” James said of the scholarship, which is awarded to only 40 of the 800 qualified U.S. applicants each year. “They are trying to create a network of leaders who are some of the best in their fields, which is why I think they have so many different levels of vetting. They are trying to find the crem de la crem—those who are specifically interested in applying their unique talents and skill sets to changing and improving the socio-political climate of the world.”

James was accepted to all of the graduate programs she applied to, but she accepted the offer at Cambridge because it is the premiere institution for studying the democratization of education.

Certainly, James’s path has been paved through her hard work, tenacity, and grit, but she is also the first to point out that without luck and a lot of support, her hard work alone would not have gotten her where she is today.

“There is a problem with propagating the idea that folks who grew up on the wrong end of the tracks, so to speak, just need to work harder,” James said. “If we tell students that they need to work harder to pay for books, schooling, and housing, then the students have to sacrifice their academic opportunities. They have to sacrifice internships, leadership opportunities, and community service opportunities—and these are the kinds of things that make them incredibly competitive for scholarships, jobs, and graduate school.

“It’s not just about hard work; it’s about communities supporting students throughout their education.”

When James came to campus in 2008, she was determined to leave her life of abuse, foster care, and disadvantage behind her. She felt the need to prove herself—to prove that she deserved the opportunities of a university education, and she didn’t want to be branded for her past; she wanted to be seen for her intelligence and her talents.

But for at-risk youth like James, determination is rarely enough to overcome the cards they are dealt in childhood. James wanted to study, but she didn’t have money for books. She wanted to learn, but she didn’t have money for food. She wanted to thrive, but she didn’t even have a place to live.

“My friends were allowing me to eat off their meal plans—and then even that fell through,” James recalled. “It was an amazingly stressful environment for me to be in school, and I remember thinking after that first semester, ‘This is not going to work for me. Perhaps college is just not for me. Perhaps this isn’t my lot in life.’”

In her first semester, James failed every course she’d signed up for as a result of her emotional and physical duress. Still, she wasn’t ready to give in. As a last-ditch effort to avoid joining the 96 percent of foster youth who don’t graduate from college, James walked into Clark Hall to meet with then-associate dean of student affairs Dr. Ann Webb.

“I remember Ann Webb coming out, and she was busy at that point, but she made the time to speak to me,” James recalled. “She very simply said to me, ‘What’s going on? Tell me about your semester,’ and I broke down crying.”

Through her tears, James explained the gravity of her circumstance and tried to make it absolutely clear that her grades were not a reflection of her intelligence or her investment.

“I knew and still know nothing whatsoever about her family circumstances,” Webb recalled of the conversation. “I remember having to really probe her as to whether or not she ate breakfast that morning—and whether or not she had had anything to eat the day before. But I did sense that this was a very, very bright young woman who was pretty much going hungry because she didn’t have people to turn to.”

Using discretionary funds and appropriate scholarships at her disposal, Webb immediately bought James a meal card and then helped to purchase her books, secure her housing, and erase the failing grades from her academic record so that she could repeat the semester with a clean slate.

“When I walked out of that office, I felt as though I had been given an opportunity to participate in an education system that was not a part of my birthright,” James said. “It was that powerful for me. It was absolutely earth shattering.”

And it wasn’t a one-time intervention on James’s behalf either.

“Dr. Webb was able to recognize, after resolving the immediate emergency, that my situation needed to change in order to keep me from going through this every semester,” James said. “She found donors who would show up for me every semester—and they did—every single semester until I graduated.”

Over her four years at The University of Alabama, James received eight scholarships, awarding her more than $11,000.

“All of the things that I was able to do—working with the mayor on diversity day, working on Alabama REACH, doing research as a McNair Scholar, and working with the Blackburn Institute—would not have been possible had someone just said to me ‘You need two jobs.’

“Dr. Webb looked at me and she said, ‘I want you to bring your best self. How can I support that?’”

The help James received, not only from Webb but also multiple faculty mentors, became part of the impetus for her participation in Alabama REACH, a UA program that helps foster youth, wards of the state, homeless youth, and others receive the resources and support they need to succeed while in school.

“I didn’t want another student to go through what I had to go through to get help,” James said. “I didn’t want them to feel the shame that I felt when I came with my arms open asking, and I knew that the help couldn’t be done in one-off silos. It needed to be built into the system—catching students before they drop out.”

In the early years of the REACH program, James served as a student voice—helping the founding leaders to understand what being a foster student is really like. She also helped to organize activities for foster youth and tried to help build their on-campus community. In the process, James said that she realized how important it was to speak about her past and be a voice for the upcoming generation of at-risk youth.

“Before REACH, I had been so focused on redeeming myself and showing people that I deserved to be at UA—because I was a leader and an intellectual—that I actually separated myself from my own narrative,” James said. “But I came to understand that if folks like me went to school and became successful but weren’t willing to talk about their gritty narratives, then they couldn’t build a system that would actually help other students to make it through school.”

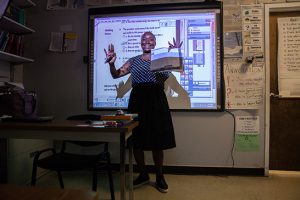

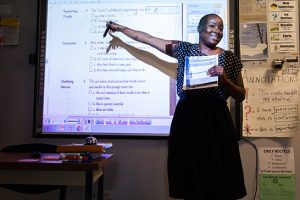

After she graduated with a degree in New College—in the top 10 percent of her class—James moved to Louisiana to teach fifth graders in low-income areas where educational opportunities are often limited.

Her focus there was to give the students the opportunity and resources to critically evaluate their world—as they might in a top-tier school elsewhere in the country. In part, James achieved this by helping her students to see themselves as leaders, whose life circumstances, though challenging and hard, had given them unique characteristics like grit that could propel them to success.

“One popular misconception about at-risk youth is that their life of hardship gives them nothing—and only depletes their spirit,” James said. “That is entirely untrue.

“In fact, a number of studies have shown that one of the most important characteristics for any leader in any industry is grit—and I think that the greatest way to develop grit is to have gone through some strife. The reality is, kids who live through the kinds of circumstances I lived through are going to be gritty people. They’re going to show up. They’re going to fight. They’re going to get done what they need to get done.”

The other part of James’s success was in situating each academic subject within the context of her students’ lives. Instead of just teaching percentages, she had her students analyze the ways that news outlets present incarceration rates. Instead of just reading books, she related the stories to things like domestic violence and women’s rights.

“I built my units to address things that get at the core of who my students are,” James said. “It stirs up conversations they would likely never have in a classroom otherwise.”

For her work with her students, James received the Sue Lehmann Award for Excellence in Teaching in 2014, and soon afterward she realized that she wanted to do more.

“I recognized that when my students would go to a new teacher the next year, they likely would not have a curriculum that would allow them to explore their world,” James said. “They would return to thinking of math only in terms of numbers and reading only in terms of facts. I wanted give them this transformational education throughout their entire educational experience because that’s what was going to change their lives.”

As a result, James shifted from teaching youth to teaching teachers. She worked in teacher development for a year and a half—helping two of her students receive nominations for their own national teaching awards—and then realized that she still had more to learn.

“It was time for me to be developed, so I began looking for programs around the world that were redefining education,” James said. “The top one was Cambridge.”

In preparation for her studies at Cambridge, James spent her summer in Chicago working as a non-profit GED instructor so that she could see the ways that education, or the lack thereof, impacts people’s lives. She also participated in and spoke at the Ten for Ten Kids Conference, which chose 100 leaders from around the United States to serve as a think tank for redesigning child welfare.

“Most of the folks who are improving our systems in the United States have already come in with an answer—even when research and ground-level interactions prove otherwise,” James said. “But I am trying to be as open as I can. I’m immersing myself in as much information as I can so that I will ask the right questions, do the right research, and come to the right conclusions about where our education system needs to go.

“I’m no longer just a first-generation college student,” James added. “I am well beyond that at this point—heading off to one of the most prestigious schools in the world with one of the most prestigious scholarships in the world—and that would not have happened without the support of people like Dr. Webb, Dr. Hawk, Dr. Black, Dr. Roach, Karen Baynes-Dunning, and other UA faculty.” ■