You’d think that spending the summer at the site of Louisiana’s oldest French settlement would be nothing short of grand. But Paul Eubanks, a doctoral student in the Department of Anthropology, tells a different story.

Eubanks’s six-week stay in Natchitoches involved daily ventures into the swamps of northwestern Louisiana and ample amounts of digging as he conducted research for his dissertation, which will focus on the history of salt production in the area.

Though he describes Natchitoches as a town akin to New Orleans, only with less debauchery and condensed into one street, he spent most of his time in the areas surrounding the historic town, areas where canoes are the primary means of transportation and where alligators, hogs, panthers, and poachers are known to roam. During one of his first trips to the research site, he hopped out of his car and found a water moccasin between his feet. The snake recoiled and scurried off into the woods.

“Fortunately it was just as scared of me as I was of it,” Eubanks says. “We had a lot to watch out for while we were there.”

Eubanks and his team of researchers excavated 10 archeological test pits from May 12-June 21, searching for remnants of life during the 17th and 18th centuries, when the Caddo Indians occupied the area and began producing salt in large quantities. The team’s research was made possible by an $18,000 grant Eubanks won from the National Science Foundation, as well as by funding he received from the Department of Anthropology and the Alabama Museum of Natural History.

Eubanks said the site was chosen because of its unique history.

“One of the main reasons why Natchitoches was established is because of the Drake’s Salt Works, which is where we were digging,” he said. “Looking at historical records, there’s a quote from the commandant of the fort at Natchitoches saying they built the trading post there because it was so close to the salt production site.”

When the water table rose, water with high concentrations of salt would percolate to the ground surface and then evaporate, leaving the salt behind, he said. The Indians then scooped up the salt when the salt flat was dry. Using this method, the Caddo salt makers were able to produce hundreds of pounds of salt each year, which they then traded to the French, Spanish, and other American Indian groups, placing them in a powerful position due to high demand for the mineral.

“Salt is something we take for granted today, but that wasn’t the case two or three hundred years ago,” he said. “Salt was called the white gold because it was something that people needed. It was used not only for dietary reasons – because you need some salt to live – but it would have been used to preserve meats and tan animal hides. During the 1700s, there was a big demand on the European markets for deer, beaver, and buffalo hides.”

The site also shows evidence of European takeover, which occurred in the early 1800s. Several dozen historic salt kilns made of brick, as well as one of the world’s oldest examples of deep well rotary drilling, were added to the site after the Caddo left the area and the Americans took over the salt works. The well, more than 1,000-feet deep and built in the 1840s, still bubbles forth salt water to this day.

Despite the site’s historical significance, little work has been done there. Only since 2011 has The University of Alabama partnered with the U.S. Forest Service to work on joint projects and learn more about the site’s history. Even so, Eubanks said it’s impossible, at least in some parts of the site, to take a step without crushing a half dozen pieces of pottery or other artifacts.

When Eubanks and his team first started the excavations, they were looking for signs of habitation that would indicate the amount of time the Caddo salt makers spent at the site.

“We were looking for domestic-related materials to see if the Indians stayed there for a period of several days, just to make salt, or if they stayed there for longer periods of time,” he said. “It looks like they stayed there for longer periods of time, but on a temporary or seasonal basis. We didn’t find any signs of permanent architecture, but we did find a lot of animal bones, which shows that they took the time to bring in meat and process it. We also found a lot of stone debris and stone tools.”

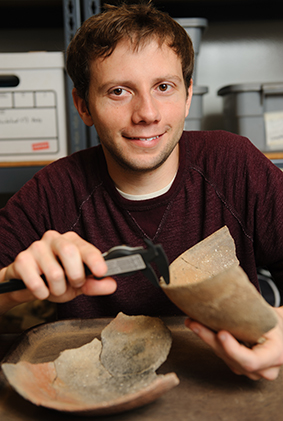

But the group also found something they weren’t expecting – thousands of broken salt bowl fragments buried beneath the ground surface in one particular area of the site. This space was used to further refine the salt.

“These bowls were quickly constructed, and their primary purpose would have been salt manufacture,” he said.

As the Indians collected the dried salt from the ground surface, they would have gathered a substantial amount of unwanted sand. To get rid of the sand, they placed the salt-sand mixture into a woven basket, collected water from a nearby creek, and poured the water over the mixture as the basket was suspended over these ceramic bowls. The water would have dissolved the salt, and the resulting liquid brine was then boiled inside of the salt bowl.

“We knew that area of the site existed, but we didn’t know how it was used,” he said. “I was excited to discover something that we didn’t know previously.”

Eubanks’ next step is to analyze the artifacts and write his dissertation. He expects to graduate with his doctorate in May 2016.