Famous for the photos he took on his small Brownie camera, William Christenberry captured a poignant vision of Alabama. In fact, in 2013, William R. Ferris, the former chairman of the National Endowment for the Humanities, referred to Christenberry as one of the three most important photographers of the South.

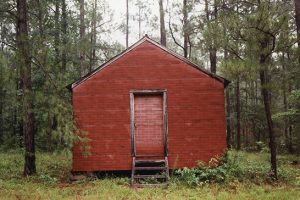

His work recorded the decay of dilapidated tenant houses and the growth of invasive kudzu in Alabama’s Tuscaloosa and Hale counties, where he was born and raised.

However, the UA graduate was far more than just a photographer. Prior to his battle with Alzheimer’s and his eventual passing in November, he spent as much, if not more, time working with paint, clay, ink, and other materials as he did with a camera lens.

“He was really fearless when it came to exp

erimenting with his work,” his wife, Sandra Christenberry, recalled. “And he always wanted his body of work to be seen as a whole—the paintings, the wall constructions, the collages, the photographs, and the Klan tableau. He is certainly best known for his photography, but he considered that just a part of his body of work.”Sandra was introduced to the experimental side of Bill early in their relationship. In fact, on their first date, in 1965, Bill mystified the young Sandra when he held a New York-style “happening” outside his studio.

It was his 29th birthday, and almost as soon as she’d arrived, Sandra was ushered back outside with the rest of the party-goers. Together, they stood in the dark at the edge of a gravel driveway, and before long a man walked up and rolled out a long sheet of white paper as though it were a red carpet. At the opposite end of the driveway, a dark green Bently covertible drove toward them carrying three people wearing white masks and dressed entirely in black.

“The car stopped, and out of the night sky came this white toilet on a rope,” Sandra said. “The young boy in the back stood up, grabbed the rope, and cut it with a knife. The toilet fell next to him, and the car drove off into the night.”

That was it. Now in darkness again, the members of the party were left to wonder. A toilet? White masks? What is this?

“I, of course, was mystified,” Sandra said. “But there was just something about his work that stru

ck me as being extraordinary.”

Christenberry’s official art education began at The University of Alabama in the early 1950s. He received his bachelor’s degree in 1958 and then his master’s degree in 1959. Christenberry was heavily influenced by his abstract expressionist professors—especially Jack Granata, Howard Goodson, and Melville Price—but he also found his own voice through his deep connection with the state of Alabama.

In his book, Working from Memory, he writes, “Abstract Expressionism was all the rage in the art world then, and just like everybody else I was painting in that style.

“I was coming to grips with my feelings about the landscape and what was in it, though, so I incorporated objects or places into my paintings, such as graveyards and tenant houses. I would take color photos with the Brownie of anything that caught my eye, send them to the local drugstore to be developed and use the photos as color references for my paintings in the studio.”

According to Sandra, however, Christenberry never considered himself a photographer. He explained in a 2009 interview with UA’s Rachel Dobson that when he was first asked to show his images to renowned photographer Walker Evans, who is famous for capturing the Great Depression on film, he was hesitant. He’d taken the pictures for his reference only. But after Evans sifted through them one by one, he told Christenberry, “Young man, that little camera has become a perfect extension of your eye, and I suggest you take these seriously.”

Over the next four decades, Christenberry would return each summer to Alabama to visit his family, be renewed by the landscape, and take more photographs. Creating a kind of time capsule, Christenberry would revisit the same sites he’d visited previously to take new pictures showing the kudzu growth or the houses and buildings further deteriorated.

“I wanted to use the subject matter that I was familiar with, that I grew up with, that I cared so deeply about,” Christenberry said in a 2009 interview at UA. “I didn’t know that earth, that red dirt—what an effect if would have on me.”

In 1968, Christenberry moved with his wife from Memphis State University to Washington D.C., where he began teaching at the Corcoran School of the Arts and Design. In 1984 he received a Guggenheim Fellowship and in 1998, he received an honorary doctorate of humane letters from his alma mater.

By 2008, Christenberry was diagnosed with a mild cognitive impairment, or MCI, which later developed into Alzheimer’s, but he continued to work in his personal studio until 2011.

“Bill’s work is so heavily influenced by growing up in the South, but though his subjects usually had something to do with Alabama, his work has universal appeal,” Sandra said. “His imagination was amazing.”